Divers find unexpected Roman inscription from the eve of Bar-Kochba Revolt

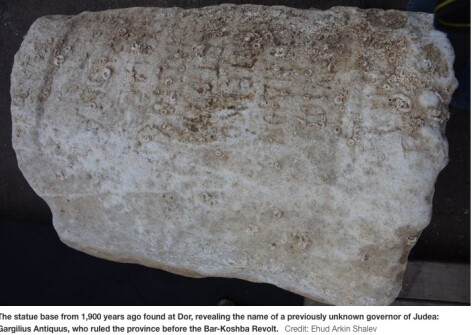

A statue base from 1,900 years ago found at Dor survived

shellfish and seawater, and to the archaeologists' shock,

revealed a previously unknown governor of Judea.

An underwater survey conducted by divers off Tel Dor, on the Mediterranean Sea, yielded an astonishing find: a rare Roman inscription mentioning the province of Judea – and the name of a previously unknown Roman governor, who ruled the province shortly before the Bar-Kochba Revolt.

Historians had thought that based on Roman records, the leaders Rome imposed on its provinces were all known.

The rock with the 1,900-year-old inscription was exposed by a storm on the seabed at a depth of just 1.5 meters in the bay of Dor. The town had been a thriving port in Roman times that even minted its own coins, which proudly proclaimed the city to be "Ruler of the Seas".

Found by Haifa University archaeologists surveying the remains of the ancient Roman harbor at Dor in January 2016, the rock, 70 by 65 centimeters in size, was partly covered in sea creatures when it was found.

"We knew that another storm would be coming within days, so we decided to extract it rather than risk the stone being reburied in the sand, or damaged," Prof. Assaf Yasur-Landau of Haifa University told Haaretz. In a joint operation with the Nature and Parks Authority and the Israel Antiquities Authority, the heavy stone was raised by divers, and taken to Caesarea for careful cleaning, a process that took four months.

Only then it was possible to read the inscription, heavily worn by the sea, and therein lay a surprise.

Gargilius Antiquus: A name set in stone, twice

The statue base found on the seabed at Dor is only the second known mention of the province of Judea in Roman inscription. The other is the "Pontius Pilate stone" dating to around 100 years earlier. Discovered by archaeologists in 1961 at the ancient theater in Caesarea, it is a rare piece of solid evidence mentioning Pilate, prefect of Judea, by name.

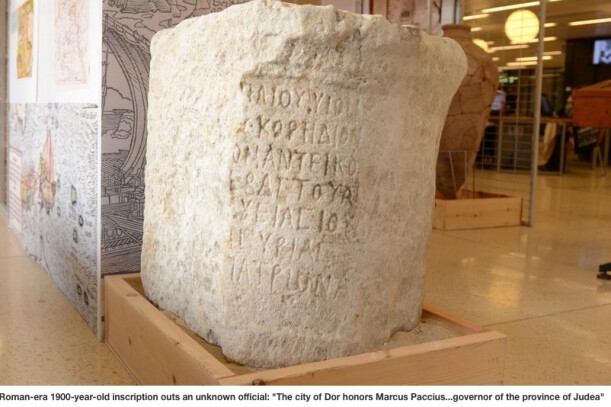

The newly found inscription, carved on the stone in Greek, is missing a part, but is thought to have originally read: “The City of Dor honors Marcus Paccius, son of Publius, Silvanus Quintus Coredius Gallus Gargilius Antiquus, governor of the province of Judea, as well

The name Gargilius Antiquus had been known from another inscription previously found in Dor – as the governor of a province whose name was missing from that inscription. So far, reconstructions have suggested either Syria or Syria-Palaestina as the province he was governing. Dr. Gil Gambash, head of the Recanati Institute for Maritime Studies, and Yasur-Landau were excited to read on the new inscription that Gargilius Antiquus was in fact the governor of Judea, shortly before the Bar Kochba Revolt.

The inscription outing Gargilius Antiquus was apparently the base of a statue, going by the tell-tale marks of small feet incretions on its top.

The putative statue has not been found, but it could plausibly have been of Gargilius Antiquus himself, who was not only the province's governor but also a patron of Dor, as the inscription states.

“A patron was somebody who contributed to the city somehow," Gambash told Haaretz. "We know of several new buildings that were constructed in Dor during this period. If the governor gave the city something, perhaps a temple, it would have been natural to honor the benefactor with the title of patron, and with statues.”

Whomever it depicted, the statue had been positioned in a public place, perhaps near a temple complex where the individual could be honored, as was the custom in the Roman Empire.

A commander of armies

In fact, this was not the only occasion Gargilius Antiquus was bestowed honors by his subjects. During Israel's War of Independence, in 1948, another statue base fragment was found at the east gate of the ancient city of Dor, with writing that reads: “Honored Marcus Paccius, son of Publius…Silvanus Quintus Coredius Gallus Gargilius Antiquus, imperial governor with Praetorian rank of the province Syria Palaestina”.

Clearly the Roman emperor, in this case Hadrian, had appointed Gargilius Antiquus as governor of the province of Judea, somewhere between 120 – 130 C.E. (perhaps around 123 C.E., succeeding Cosonius Gallus).

The word "pro-praetor" had a military tang to it: This Gargilius Antiquus was not just an administrator or a revenue-raiser, but also, when required, a commander of armies and a fighter on horseback on the wilder fringes of the empire.

It is perhaps odd that his name hadn't been seen before in the context of Judea. Governors regularly communicated with the emperor. Matters involving his dignity or any threats to Roman authority required reports, and resulted in imperial orders. A governor might be anxious to give the emperor his own version of events in his province before others could complain. With trouble brewing in Judea, which would soon erupt in the Bar Kochba Revolt – such concerns would have been very real to Gargilius Antiquus.

Gargilius Antiquus would have commanded two legions with 3,000 to 5,200 men each, as well as a cavalry regiment likely consisting of 500. His soldiers routinely impaled lawbreakers. In peacetime, executions followed summary hearings, but during an uprising, rebels were put to death on the spot and en masse. For example, the Romans impaled 6,000 slaves to crush the revolt led by Spartacus.

His reign spanned critical years before the Bar-Kochba Revolt, when Jewish dissatisfaction with Roman rule was brewing. Most notably, a Jewish revolt against the Emperor Trajan exploded in Egypt, Cyrenaica (Libya), and Cyprus in 115-117 C.E., and ended less than a decade before Gargilius Antiquus came to rule Judea.

Gargilius Antiquus may well have been the last Roman governor of Judea per se. The Romans changed the province's name to Syria Palaestina after the Bar Kochba Revolt was crushed, to further eliminate the Jewish identity of the land.

Whatever happened to Gargilius Antiquus?

Originally, Gargilius Antiquus may have come from North Africa. His name suggests that he belonged to the tribe of the Velina — nobles from northeastern Tunisia, long established in the Roman senate. Ancient sources reveal that he began his career in the far-flung Roman territories as a relatively junior governor, in Arabia, somewhere after 115 C.E., during the reign of Emperor Trajan.

Such governors were men of the so-called equestrian order—the lower nobility, as opposed to aristocrats of senatorial status. Governors of Gargilius Antiquus' rank were usually sent to barbarous territories. The Romans considered Arabia to be such a place.

How long Gargilius Antiquus held the position as governor of Judea is unknown. What is clear is that he was a successful one, at least as far as the Romans were concerned. Following his Judean stint, he was appointed proconsul of the newly established province Syria-Palestina and around 135 C.E., was appointed proconsul of Asia, the last and highest position in a senatorial career.

How the Jews felt about him isn't known, since the fact of his governorship in Judea had not been known either. All we do know is that in the city of Dor, which had a minor Jewish community, he was honored at least twice, Gambash says.

It is small miracle that the stone should have survived at all. The sea could have worn the lettering away. Builders subsequently using it when the statue itself had fallen into ruin could have recut it in such a way that the name was illegible. It could have been discarded as rubble and never recovered. As it is, it seems almost incredible: archaeologists found a barnacle-encrusted but irrefutable physical link to a man who governed Judea some 1900 years ago.

The Roman inscription will be on display at the Haifa University Library.